Summer is time and space, writing and silence. Of all this makes a song for the summer, mixed with almost nothing, because all music is hostage to silence and lives only for as long as it evades it: a song that was born in Italy and has become everyone's and no one's, because it has become attached to those who adopted it, like a lost puppy, and now it wanders the world, caught up in the mills of memories.

Estate (Summer) is from 1960, the year of the Rome Olympics, the games with the sprinter wearing glasses and the barefoot Ethiopian and the boxer who would later change his name and religion. Writing the lyrics, in a hotel room in Naples, was Bruno Brighetti, a multi-instrumentalist from Bologna who played woodwind and accordion in the band led by Bruno Martino, a 35-year-old pianist from Rome with a jazz background, who had ended up behind the microphone by accident due to the lack of a vocalist, and then never stopped, making a decent fortune playing in clubs in Northern Europe. Far from the Italian sun.

Newly set to music, it was called Odio l’estate (I Hate Summer) and went almost unnoticed; in the early 1960s, that bitter song hardly fit in with the collective mood, it was the story of a love that soured so badly in summer that he couldn’t wait for winter to arrive, when snow would cover everything and perhaps bring some peace. There was also the parody by Lelio Luttazzi, Odio le statue (I Hate Statues), which was also shelved.

Thus, time passed, far a greatest hit, Bruno Martino became a garrulous and mild-mannered Jep Gambardella of music, a secluded performer of soundtracks, a friend of Sandro Ciotti who wrote songs for Jannacci, a guy who watched a great future pass him by at the window behind the backs of others. He alternated between sentimental songs and ironic, sci-fi, noir tracks, as if he was still searching for the right genre for his talent. Or perhaps he was still searching for his Summer, or rather for someone else who could understand it.

Then came 1977, which in Italy meant autumn all year round, leaves of lead and the wood of gun butts. Certainly not the most congruous era for rediscoveries. Yet along came a subdued Latin American performer, João Gilberto Prado Pereira de Oliveira, who rediscovered Estate almost by accident and gave those notes the soul of sad cheerfulness of his homeland Brazil, whispering the words while plucking the strings of a guitar, turned bossa nova as if it had always been his.

After João Gilberto's orphic and nocturnal version, Estate became part of the repertoire of the greatest jazz musicians, what is known as a “standard”: a track you simply have to perform. Maybe it's not about the big numbers; the million-record, stadium-concert, star-on-stars artists didn't sing it. However, it still reached the voices and instruments of jazz greats, because Martino came from jazz and to jazz he would return with that song so long gone that another had taken its place: “And they call it summer, this summer without you,” another sentiment entrapped in reality, too sophisticated to survive in the real world.

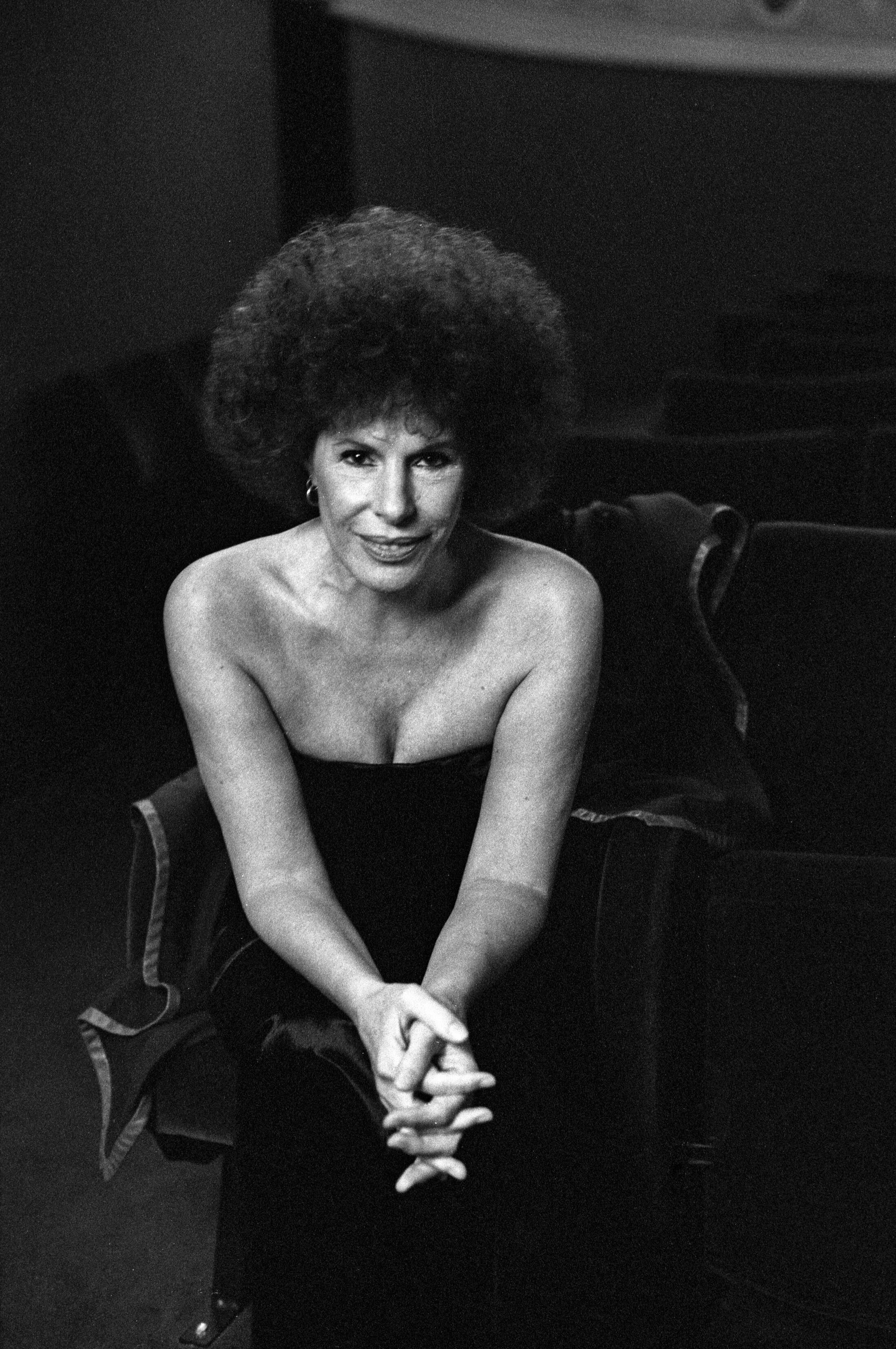

But there was the other Estate, now rarefied and reduced to its Zen essence, bordering on absence and exile. Over the years it has been sung by Mina and Shirley Horn, Helen Merrill and Ornella Vanoni, as if its secret could only be decoded by a female voice; then, among the most recent, there was Vinicio Capossela, with his nocturnal, almost lycanthropic interpretation.

However, there are three versions of Estate that shine in the darkness, melancholy and mystery of a song made to be sung and instead are played on piano, harmonica, and trumpet.

The piano version was by the French pianist Michel Petrucciani, an enfant prodige who sought refuge in an outsized keyboard, his body ravaged by illness: capable of conjuring up with his instrument the dusky desert of Ellington, with an enchanted fury, yearning for the Bach he would never play. He was a virtuoso out of desperation Petrucciani, excessively so out of debt to his Neapolitan ancestors, yet he took Estate and turned it into a subdued elegy, with the notes of his Steinway muffled by Furio Di Castri's double bass and Aldo Romano's brushes, notes like crystal tears dripping from the soul of an artist who knew he didn’t have time for everything he wanted to do.

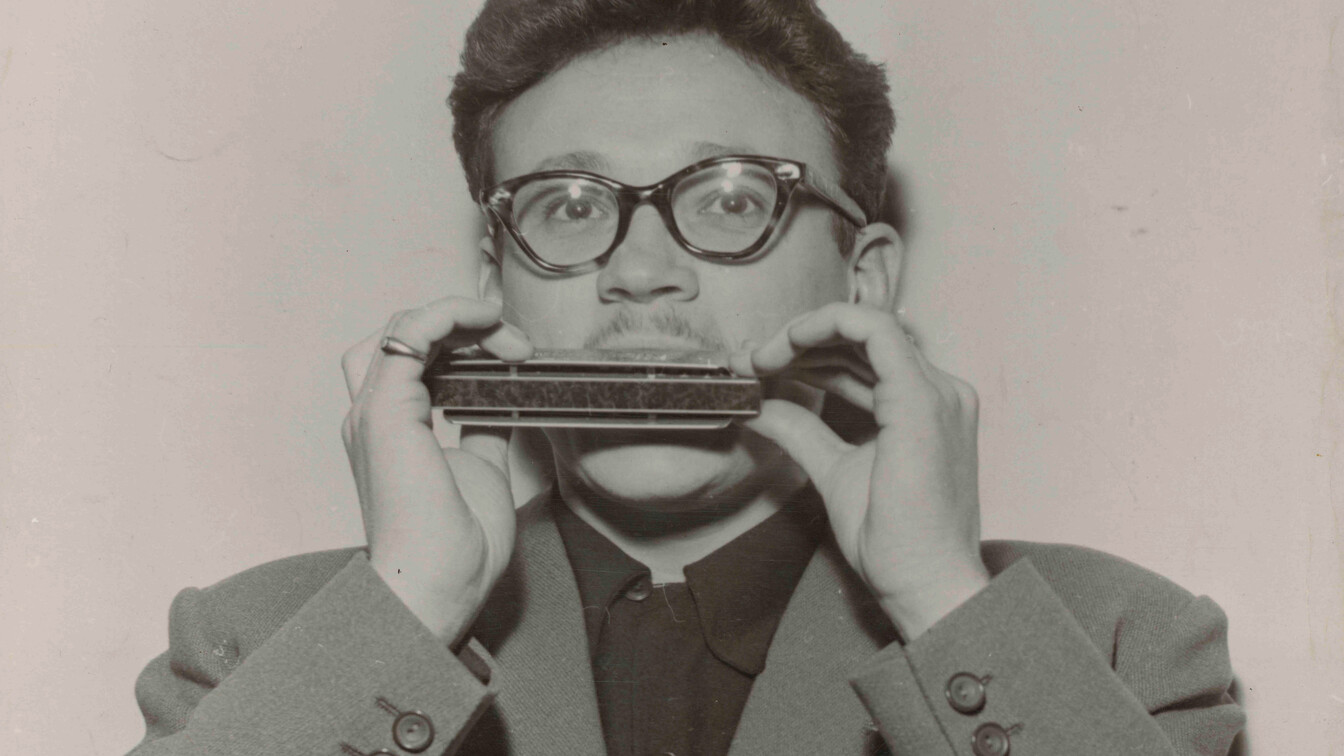

The harmonica version was by Jean Baptiste “Toots” Thielemans, who was perhaps late in arriving at Estate – at almost seventy, long after he had accompanied Mina in the theme song for [TN: the TV show] Milleluci – but he managed to grasp the darkness of the music, the emptiness and vertigo, sounding note after note as if he were painting, letting the song fly out of the grooves of the record, incomplete and fragile.

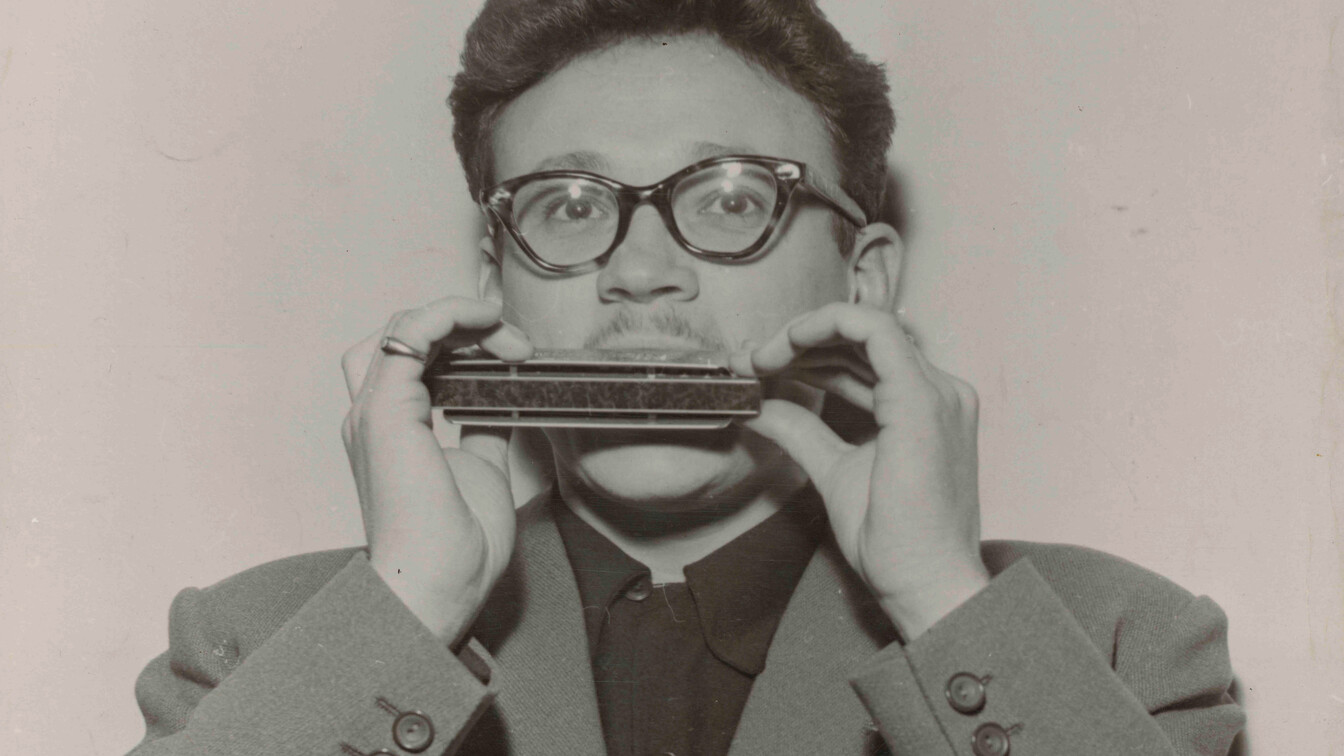

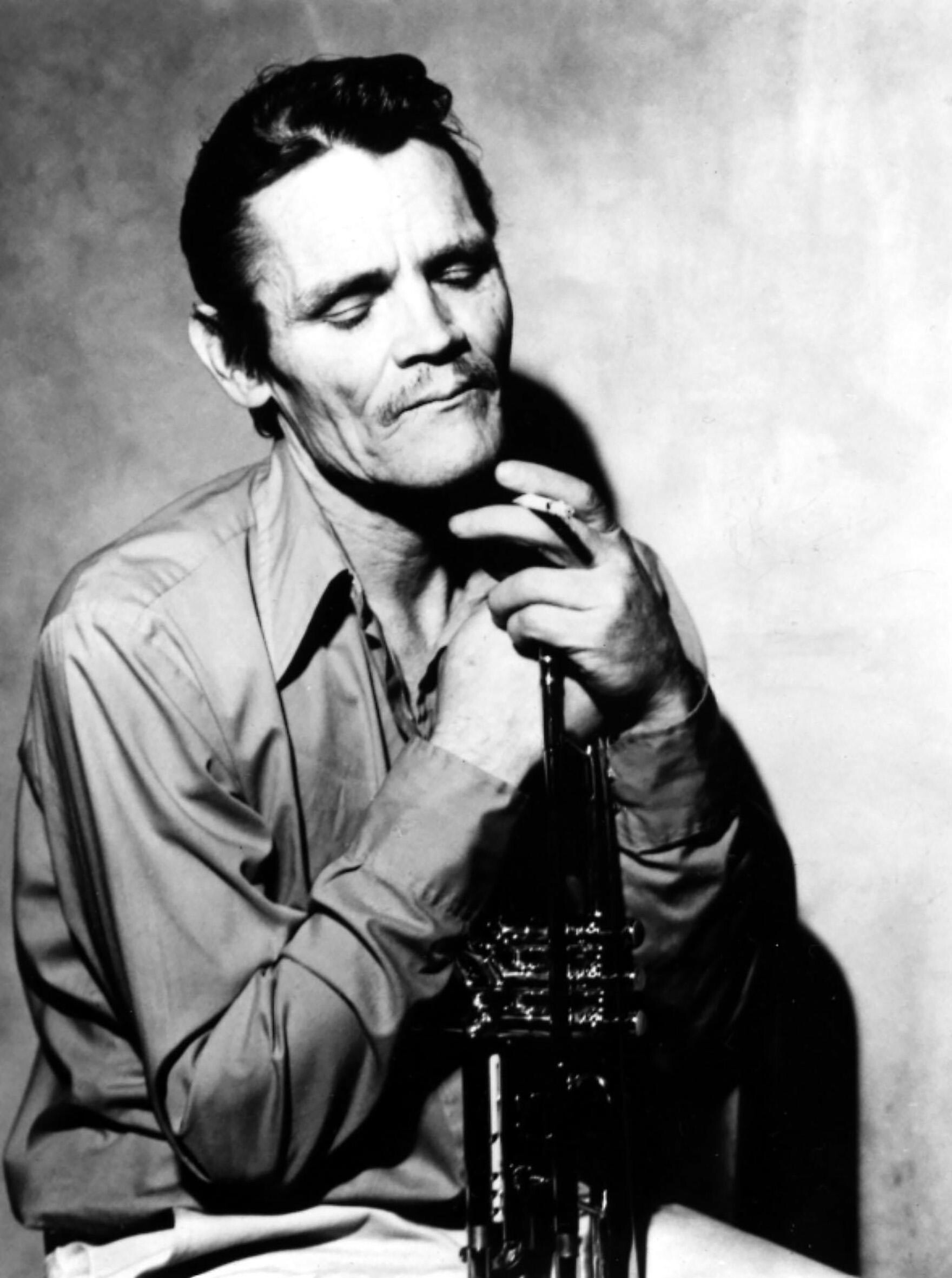

Finally, there was a handsome and unhappy trumpeter who loved Italy. And in Milan, there was a club on the Naviglio Grande, called Capolinea because it stood near the end of the line of tram 19. The best jazz musicians in the world used to go there to play, and not in the summer but in the fall of forty years ago, Chet Baker played there with his band at the time, a flute and soprano sax as well as piano, bass and drums. The owner of the club understood that it would be something big and agreed to record the concert. Chet did not have much time left; five years on, and he would fall from a hotel window in Amsterdam. Yet that night, opening the concert, he played the most beautiful and poignant and edgy and Christmassy version of Estate, opening and closing a remorseful sequence of solos by his musicians, as if as a form of farewell, as if according to a testament. It was then that Bruno Martino, almost old and now forgotten, knew he had written something that would remain. Beyond human forgetfulness, beyond their superficiality. His Estate is still here, beyond the deceptive and fraudulent course of passing time.