She was a Circassian, and she was a slave.

Carlo Vecce is the author of a fictionalized biography of Caterina, mother of Leonardo da Vinci, published by Giunti Editore. A fascinating and captivating story that comes about following the discovery of important unpublished documents. These texts shed light and close the chapter on the mystery of Leonardo’s origins, within a multi layered and complex debate.

A swamp at the mouth of the Don River, on the Sea of Azov. One morning in July. A girl is dragged away from her homeland, enslaved, sold and resold as an object by human traffickers. When she arrives in Italy, she is on the lowest rung of the social and human ladder, without voice or dignity. They stole everything from her - her body, her dreams, her future - but she will prove stronger than them: she will suffer, fight, love, give her life and regain her freedom.

It seems like a modern tale, not a story of a distant and fabulous past. This is what shocked Carlo Vecce, a well-known and esteemed researcher and scholar of Leonardo's life and work. One day, a new document forced him to go back on the trail of Leonardo's mother Caterina, and to look at things in a completely different way. Gradually, from other documents and manuscripts, there emerged signs of forgotten existences, of lives interwoven by the forces of chance or destiny. Real people, not fictional characters. Adventurers, prostitutes, pirates, slaves, knights, gentlewomen, peasants, soldiers, notaries. Their stories go back from Vinci to Florence, from Venice to Constantinople, from the Black Sea to the wild highlands of the Caucasus.

Leonardo is known to be the natural son of a young notary from Florence, Piero, and a woman called Caterina. Almost nothing was known about her, except that she was married to a farmer called di Vinci shortly after Leonardo's birth. The only certain thing is that, in the formation of her son's extraordinary inner world, of his inexhaustible search for knowledge and freedom, his mother must most certainly have been a decisive figure. She is the true mystery of his life.

For some years, the hypothesis circulated that Caterina was a slave: until now, this idea was poorly documented, though not far-fetched. The modern slavery that reached the Americas was born in the Mediterranean at the end of the Middle Ages. A little known, embarrassing, wantonly forgotten story, because it was also perpetrated by us Italians. Big business for merchants from Venice and Genoa: male and female slaves, known as 'heads' in the documents, were more profitable than spices and precious metals. In Florence, the demand was especially high for young women, destined to serve as maids, carers, and even concubines, sexual slaves, who, in the event of pregnancy, continued to be useful even after giving birth by nursing the infants of their masters.

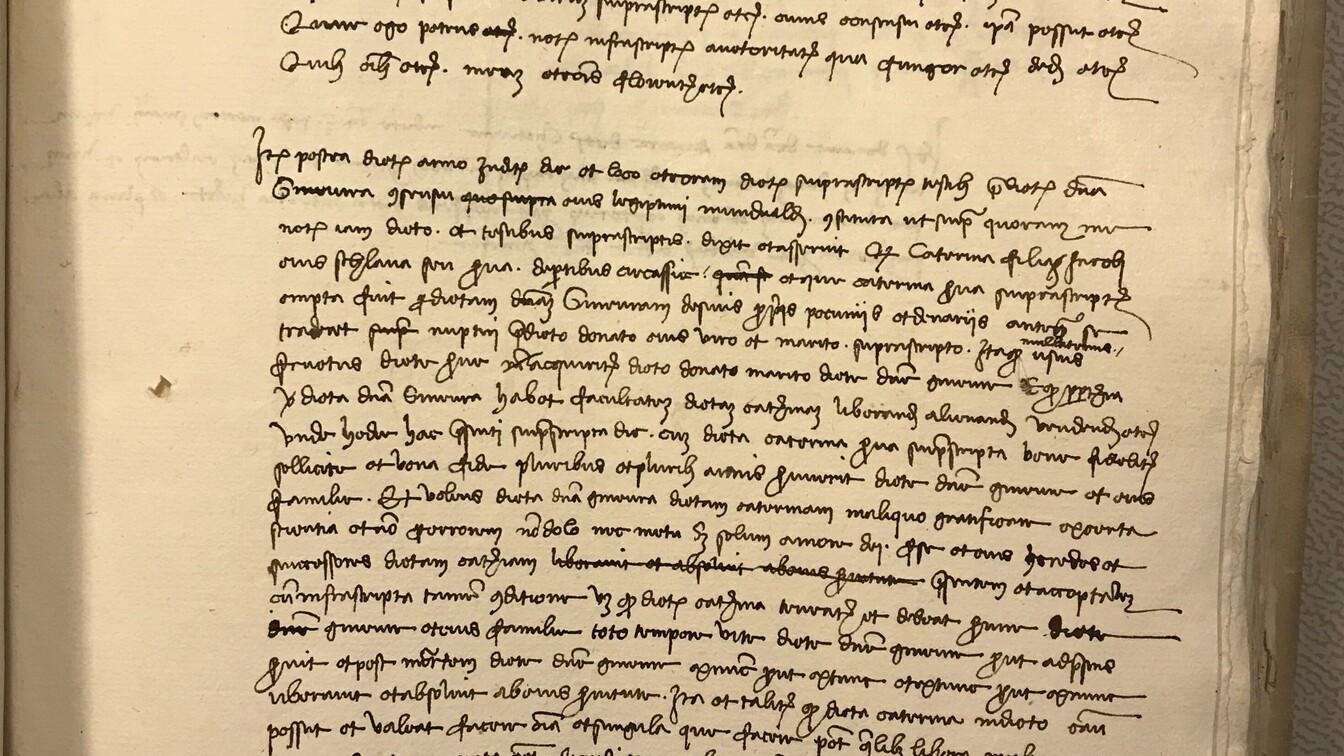

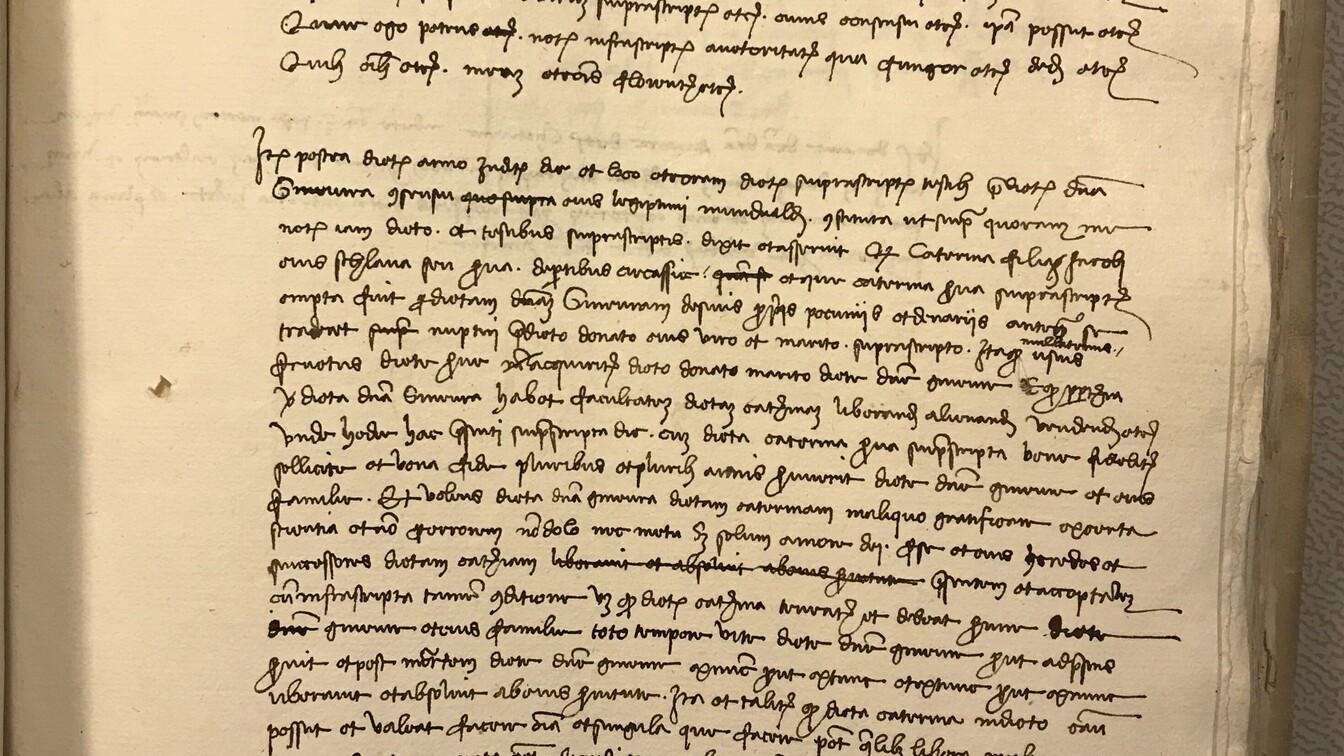

The hitherto unknown document that Carlo Vecce found in the State Archives of Florence is the deed of liberation of the slave Caterina by her mistress, monna Ginevra, who had rented her out as a wet nurse two years earlier to a Florentine knight. The document is signed by the notary Piero da Vinci: Leonardo's father. We are in an old house in Florence, behind the cathedral of Santa Maria del Fiore, in early November 1452: Leonardo is only six months old, and he is certainly there too, in his mother's arms. Rarely, in the writings of the young but already precise notary, are there so many errors, so many oversights. That slave is 'his' Caterina, the girl who gave him her love, and that child is his son. Piero's hand is shaking, overcome by an unfamiliar emotion. Not even the date is written correctly, so agitated was he on that day.

How did Caterina arrive in Florence? Thanks to her mistress's husband: an old Florentine adventurer named Donato, who had already emigrated to Venice, where he was served by slave girls from the Levant, the Black Sea and the Tana. Before dying in 1466, Donato left his money to the small convent of San Bartolomeo a Monteoliveto, outside Porta San Frediano, for the construction of the family chapel and his own burial site. The trusted notary was the same Piero. And Leonardo produced his first work precisely for that church: the Annunciation. It is not by chance.

Piero da Vinci attests that Catherine is the daughter of Jacob, and is a Circassian. Her origins trace back to one of the freest, proudest and wildest peoples on earth. She is Leonardo's mother, it is she who raised him for the first ten years of his life, and the consequences of this revelation are astounding: Leonardo is only half Italian. For the other half - perhaps the better half - he is the son of a slave, a foreigner who could neither read nor write, and who barely spoke our language. What lullaby did she sing to him to send him to sleep? What did she tell him about her origins, the fabulous places where she was born, the primordial sagas of her lost people? Of one thing we can be sure. It was she who gave him his respect for and veneration of life and nature, and an inextinguishable desire for freedom. It is she who left him the sweet and ineffable smile that Leonardo pursued his whole life, and which he thought he had found in the face of a Florentine woman called Lisa.