Hundreds of years of poetry and art in the praise of the beauty of spring were undermined by the killjoy Igor Fëdorovič Stravinskij. He wasn't content with having invented a clashing thirteenth with constant changes of accent: no, he just had to overdo it, distorting every rule, and he composed an entire ballet around that harsh and uncomfortable harmony. But what a spring, though! Nothing ever seen or heard before. On May 29, 1913 at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées the orchestral powerhouse of the ‘Sacre du printemps’ cleared the artistic scene of the tender shoots, the budding flowers, the wafting fragrances, the chirping of birds and the sighs of lovers as their senses awakened, bursting onto the scene with the paintings of pagan Russia, the wild energy of the rebirth of Nature, the propitiatory rites and orgiastic atmosphere of the sacrifice of a virgin to render Mother Earth fertile again after the barren winter.

A few years earlier (1891), Paul Gauguin, in the middle of the Symbolist period, had associated the awakening of spring with the loss of innocence, represented by a flower held in the right hand of a reclining, young naked woman while she caressed a fox, in turn a representation of lust.

With the explosion of physical sensuality and a primordiality freed from conventions and patterns, Antonio Vivaldi's ‘Spring’ had suddenly become a legacy of Arcadia, a light and graceful idealization of the seductive but not erotic magnificence of the season full of color that moves away from the blacks, whites and grays of winter with the return to light and warmth. A whole world has celebrated the cycle of life, making it a synonym for the most beautiful season, spring, like a garden of maturity, the green years as the best of all existence, the sprouting of plants, animals and human beings. The new splendor, the Latin ver, just to not go too far in time and space.

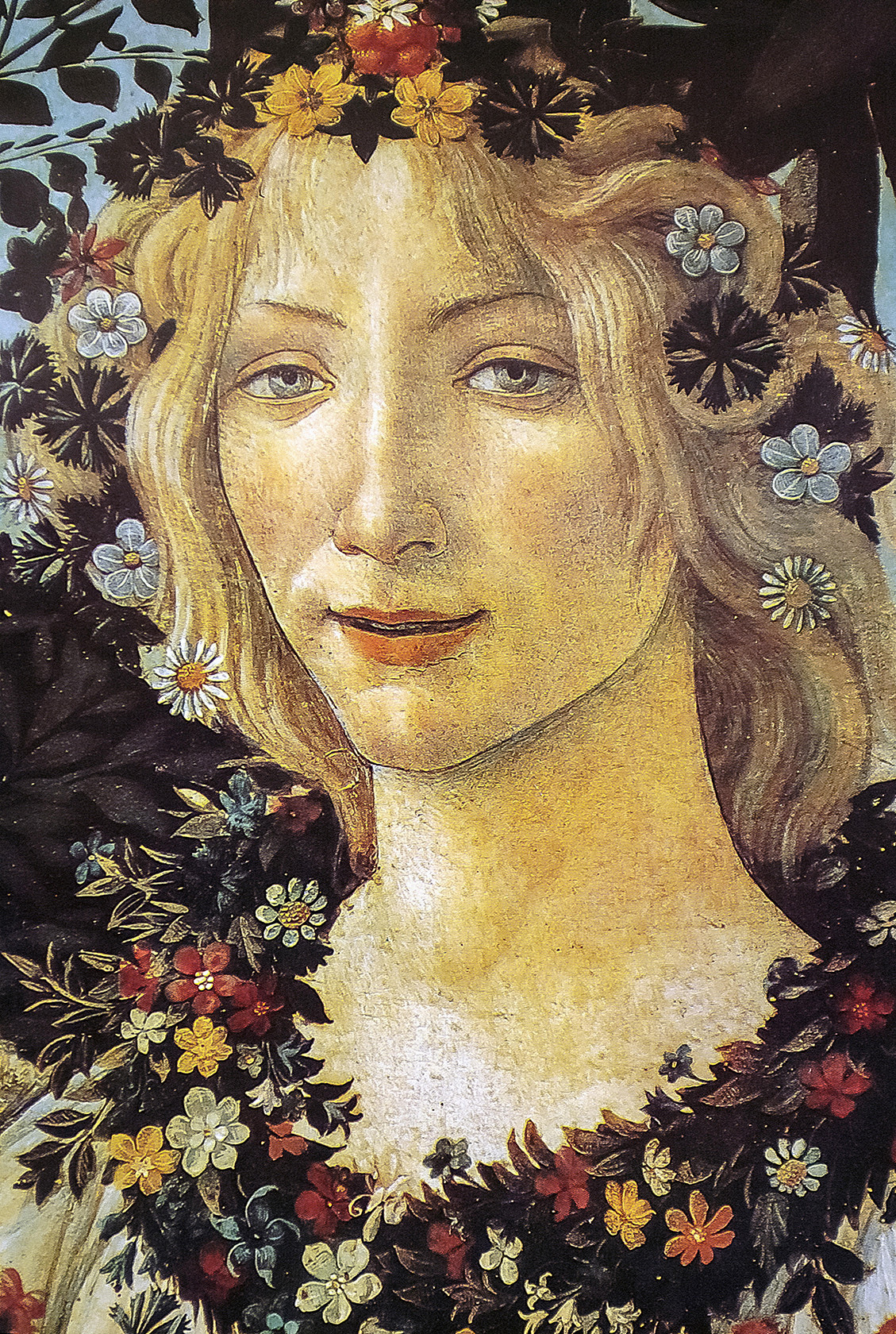

Sandro Botticelli synthesized myth, allegory and representational interpretation in ‘Primavera’ (1481-1482), a humanized triumph of the garden in bloom, the wind, fertility and the senses, with the dancing girls and with the love that omnia vincit. A dream that embodies reality by transfiguring it into an ideal tendency towards perfection, of lights without shadows and weightless bodies. A universal and absolute archetype, which represents that which does not exist but which is perceived with sensations such as to inspire many centuries later another contemporary of Stravinsky, Ottorino Respighi, with the first of the symphonic works that make up the ‘Botticelli Triptych’ (1927).

Rebirth and Renaissance, classical and classicism. The unrivaled virtuosity of the amazing assemblages by Giuseppe Arcimboldo (1563) offer the synthesis of spring as a woman of flowers (which will become fruits in summer), petals, buds, berries, corollas, leaves: female nature and femininity released by the luxuriance of its forms. Spring is female, and not just because we say so, in Claude Monet's painting (1871), which depicts his wife Camille Doncieux in a play of sunlight and shadows that makes the fluffy white dress stand out against the greenery of their garden, while the young woman is intent on reading. The white of women's clothes and the green of the surrounding nature instead constitute the leitmotiv of his interpretation of ‘Springtime’ in 1886. But with ‘Fields in Spring’ (1887), the female figure returns to the background, in a soft and no longer dazzling light, with a solemn gait in the shelter of a parasol in the fields awash with colors and under the soaring poplars. In 1882, Édouard Manet immortalized an even younger woman, beautiful and radiant in her fashionable flowered dress and with her charming parasol, a painting that the Paul Getty's Museum bought for the record sum of USD 65 million.

From impressionism to the suggestionism of Vincent Van Gogh, enraptured by the flowering fruit trees in Provence, to the extent that he dedicated 14 paintings to the most explosive sign of spring. His painting of ‘Almond Blossom’ (1890) is not a photograph of reality but a successful attempt to capture its life-giving energy through color and to express them as if the white blossoms were about to burst out of the two-dimensional azure sky.

From nineteenth-century flowers to the floral Art Nouveau, in the Mitteleuropa of Alfons Mucha (1896), in the composition with clear and bright lines, almost like a cathedral window, of spring embodied by a woman in a virginal but sensual dress caressing the taut strings on an arched branch with the counterpoint of three birds in the almost dynamic tangle of red foliage that soar in the wind. A decade later, with ‘Blumengarten’ (1907), Gustav Klimt used flowers alone to express the regenerative vigor of spring, which bursts forth in a variety of colors within the green meadows, a notion he returned to in ‘Giardino italiano’ (1913).

Futurism, with its liberating overturning of order and academia, embraced the revolutionary inspiration of Stravinsky, offering a singular reinterpretation of spring as a pure expression of form detached from any descriptive echo. Giacomo Balla, in a small oil on canvas in 1916, drew dynamic curves of green stretched out into the blue of the sky, pure vitality for meditating on the season that dismantles the rigidity of winter. And despite poetry, painting and music, which has elected spring as their number one preference, perhaps Ennio Flaiano was not entirely wrong when he wrote: “There is only one season: summer. So beautiful that the others go around her. Autumn remembers her, winter invokes her, spring envies her and childishly tries to spoil her.” Most of the time succeeding-with the irresistible force of art.